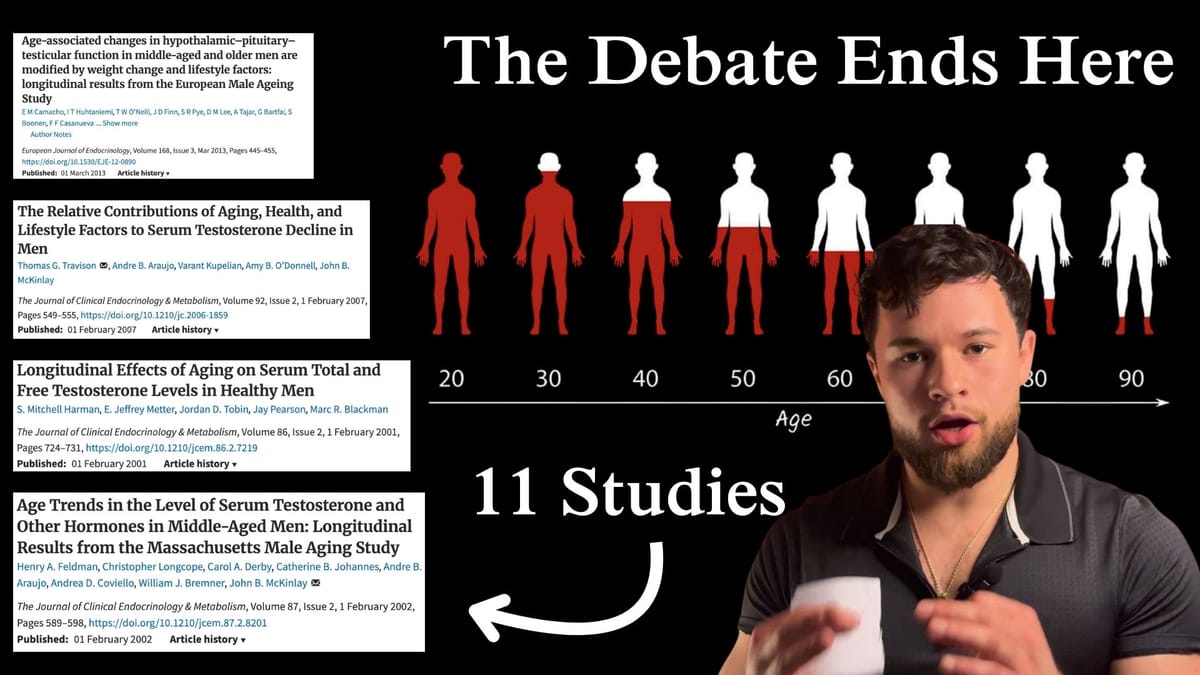

Does Testosterone Really Decline With Age? (Findings From 11 Studies)

After spending hundreds of hours over four months voraciously researching and writing this article, I can say with confidence that the article before you is unquestionably the most comprehensive overview of the scientific literature on the relationship between testosterone levels and aging you will ever read.

Why did I bother?

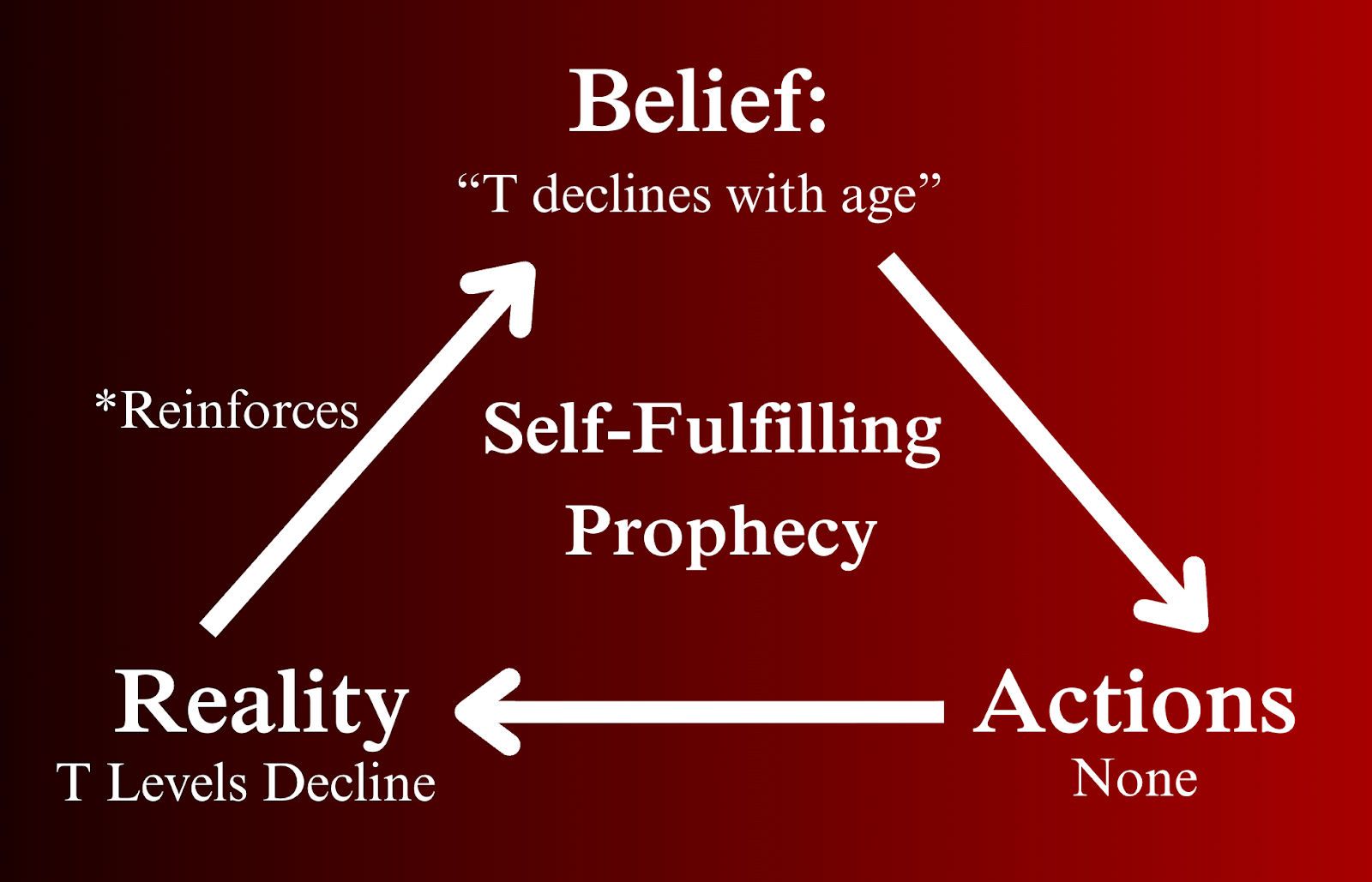

The widespread belief that testosterone declines with age causes many men to assume that they have low testosterone just because they’re getting older, and that there’s nothing they can do about it.

TRT companies are happy to capitalize on and propagate this narrative, as evidenced by this commercial claiming that their product will “build back the testosterone you’ve lost with age,” which fundamentally assumes that testosterone decline with age is a certainty.

I find this to be problematic, not only because it’s out of alignment with the science, but also because the long-term safety and efficacy of TRT in older men has not been established (5).

In another article, I spoke about how the limiting belief that testosterone declines with age can create a dangerous self-fulfilling prophecy.

The best way to overcome a limiting belief is through exposure to evidence that challenges it, and that's where this article comes in…

The purpose of this article is to objectively review the most prominent studies on this topic so that the scientific truth is accessible to anyone interested in seeking it.

I wanted this article to serve as a reference guide wherein all of the most useful research on testosterone decline with age is compiled in one place.

That way, readers who are interested in taking measures to minimize testosterone declines with age can interpret the findings in a way that is easily and quickly understandable.

Without further ado, let’s dive right into the question you came to have answered…

Do Testosterone Levels Really Decline With Age?

If I had to answer this question in one sentence: While total testosterone does not decline with age, free testosterone does, but declines typically don’t become significant until geriatric years in healthy men, and most importantly, they can be minimized by living a healthy lifestyle, because age-related reductions in testosterone are primarily the consequence of comorbidities that accumulate over time, whereas aging itself is a relatively minor contributor.

That’s the general consensus I’ve come to based on the 11 studies summarized below.

Note that there are countless studies on this subject, so in writing this article, I’ve excluded many of them to concentrate on those that are considered “landmark” studies; studies that introduce a groundbreaking finding, provide a unique perspective, or are particularly strong in terms of their scale and experimental design.

In my best effort to balance scientific integrity with reader comprehensibility, I’ve summarized the key points of each study as succinctly as possible in accessible language so that you can extract the take home message without being overwhelmed by extraneous detail.

Since many of these studies build off one another, I also weave them together into an overarching narrative that connects the findings between them.

Before we go any further, I’ve left a key below that you can refer back to when you encounter these terms throughout the article.

Terminology Key

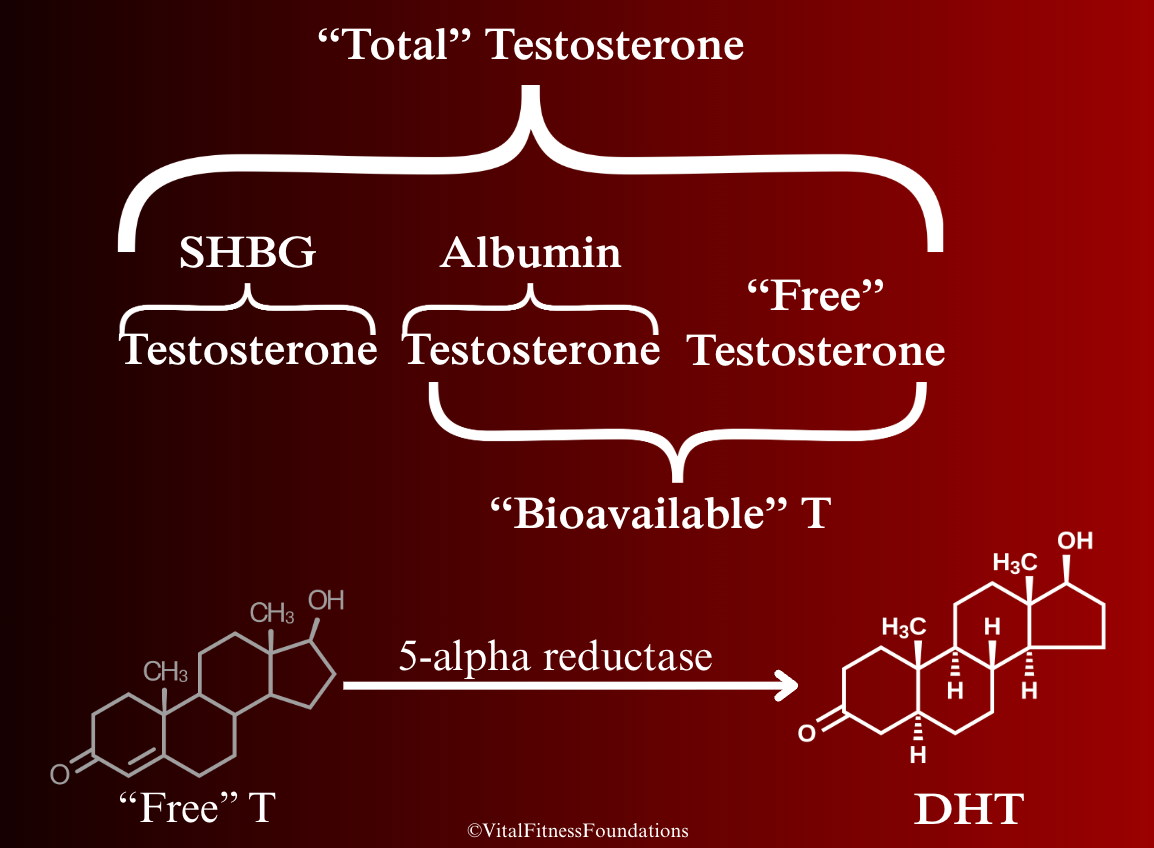

Total Testosterone (TT): Represents all the testosterone in the blood, however, most (~98%) is attached to proteins called SHBG or albumin, which keep testosterone inactivated until it’s released.

Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG): A protein that tightly binds testosterone, reducing how much can be used. SHBG levels tend to rise with age, which lowers free testosterone. But it’s not as simple as SHBG = bad. SHBG is a key regulator of testosterone and has important functions of its own.

Albumin: Similar to SHBG, albumin is a protein that binds testosterone and reduces its availability, but since it has a weaker binding affinity, albumin bound testosterone can be used much more readily by the body than SHBG bound testosterone.

Free Testosterone: The ~2-3% of total testosterone that’s not bound to SHBG or albumin and can immediately exert testosterone’s biological effects.

Bioavailable testosterone: Includes free and albumin bound testosterone, representing all testosterone that is available for near immediate use.

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT): The most potent androgen in the male body, it can be thought of as “testosterone on steroids.” DHT is created when testosterone is broken down by an enzyme called 5-alpha reductase and subsequently converted into DHT.

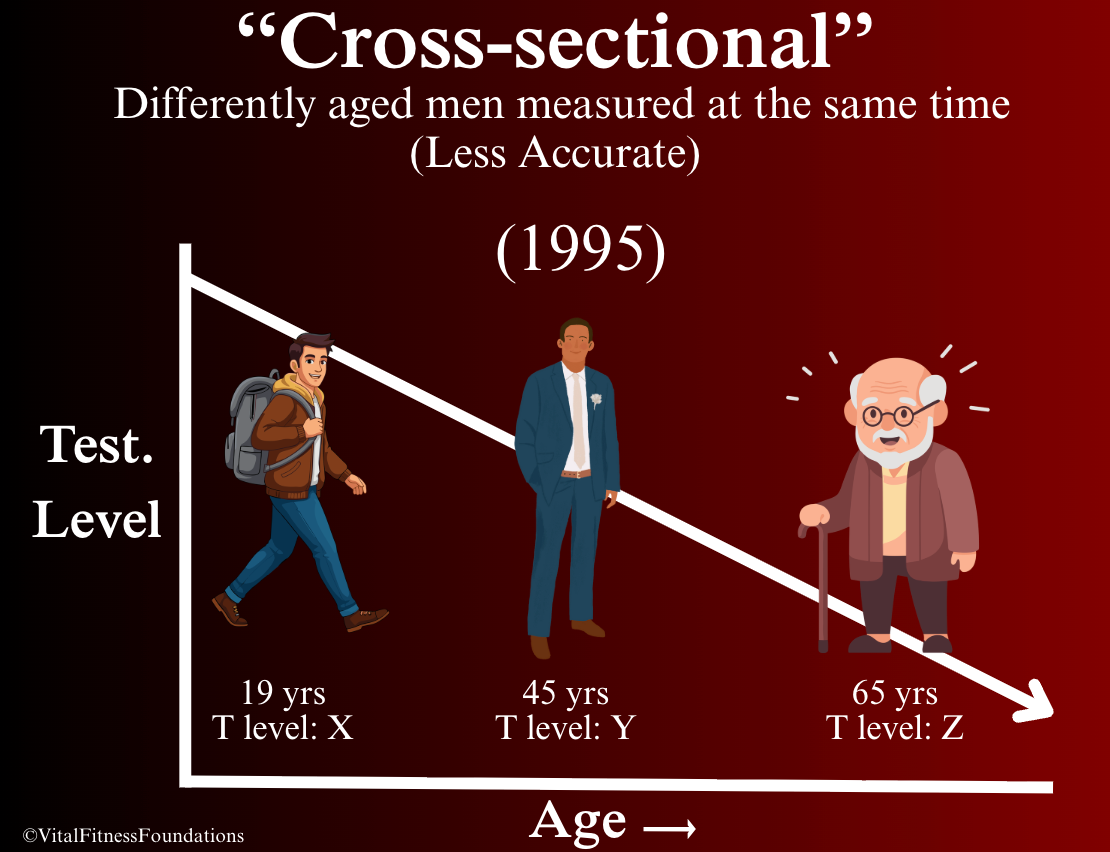

Cross-Sectional Study:

Compares testosterone readings from different men of various ages at one point in time. For example, a cross sectional study might examine the testosterone levels of older and younger men in the year 1995 and observe that older men have lower testosterone levels than younger men. Cross sectional studies are limited by the fact that they don’t track changes within the same individuals over time, so that study could only show that testosterone levels happen to be lower in the older men who were tested, not necessarily that testosterone declines with age.

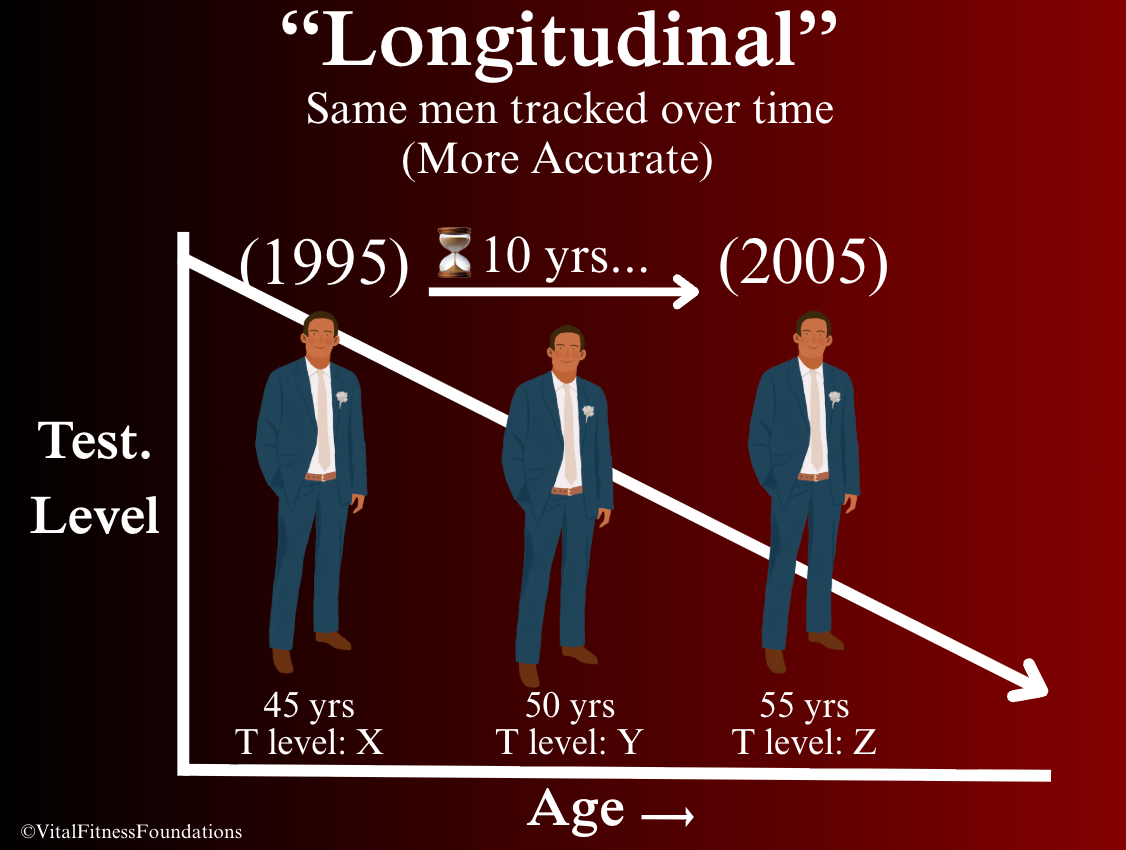

Longitudinal Study:

Tracks the testosterone levels of the same subjects over an extended period. For example, a longitudinal study might track the testosterone levels of each participant every 5 years across a 10 year timespan to determine how testosterone levels change within individuals across that timeframe.

Longitudinal studies are more accurate than cross sectional studies because they allow for more direct cause and effect associations to be established. If testosterone levels are lower in the same man as he ages, it’s more likely that those changes are caused by age, rather than random differences between different men.

The longer a longitudinal study runs for, time investment, cost, and risk of participants dropping out all increase, so longitudinal studies often have to be kept shorter than would be ideal to observe long-term changes in testosterone levels. For example, a two-year longitudinal study on testosterone decline with age doesn't allow much time to elapse to observe noticeable changes.

Although longitudinal studies can depict causal relationships with more precision than cross-sectional studies, these relationships can be exaggerated by confounding variables…

Confounding Variable:

An external factor that can distort the relationship between other variables in a study, leading to incorrect conclusions about whether one variable is truly causing a change in the other variable. For example, if a longitudinal study shows that testosterone levels go down as men get older, but many of those men become obese as time goes on, then the effect of obesity would have to be subtracted to isolate the effect of aging alone.

In the research described in this article, comorbidities are the most common confounding variables that influence testosterone levels with age.

Comorbidity:

The simultaneous presence of one or more diseases or medical conditions (e.g. obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, etc).

"Significant" Doesn’t Always = Big:

In statistics, "significant" just means that a result is unlikely due to random chance, it doesn’t necessarily mean the effect is large. A result can be “statistically significant” but still represent a very small real-world change. For example, a study may show a “significant” drop in testosterone of just 5 ng/dL per year, noticeable in data, but not necessarily impactful for health or symptoms.

The Story of Testosterone & Aging Research

The story of serious research on testosterone and aging begins with the Massachusetts Male Aging Study (16) and the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) (15). These were two major research initiatives launched to investigate the effect of aging on numerous health metrics, including hormones like testosterone.

Preliminary cross sectional studies showed lower free and total testosterone levels in older men (9), but given the limitations of cross-sectional studies, two follow-up longitudinal studies were conducted to substantiate these findings, and were the first to show strong evidence for the notion that testosterone levels decline with age. Those studies are described below…

Longitudinal Effects of Aging on Serum Total and Free Testosterone Levels in Healthy Men (Harman et al., 2001)

Design

This study analyzed stored blood samples from 890 men enrolled in the BLSA aged 19-91 years old over a 34 year timespan between 1961 and 1995. Follow-up samples were collected every two years across the duration of the study.

Key Findings

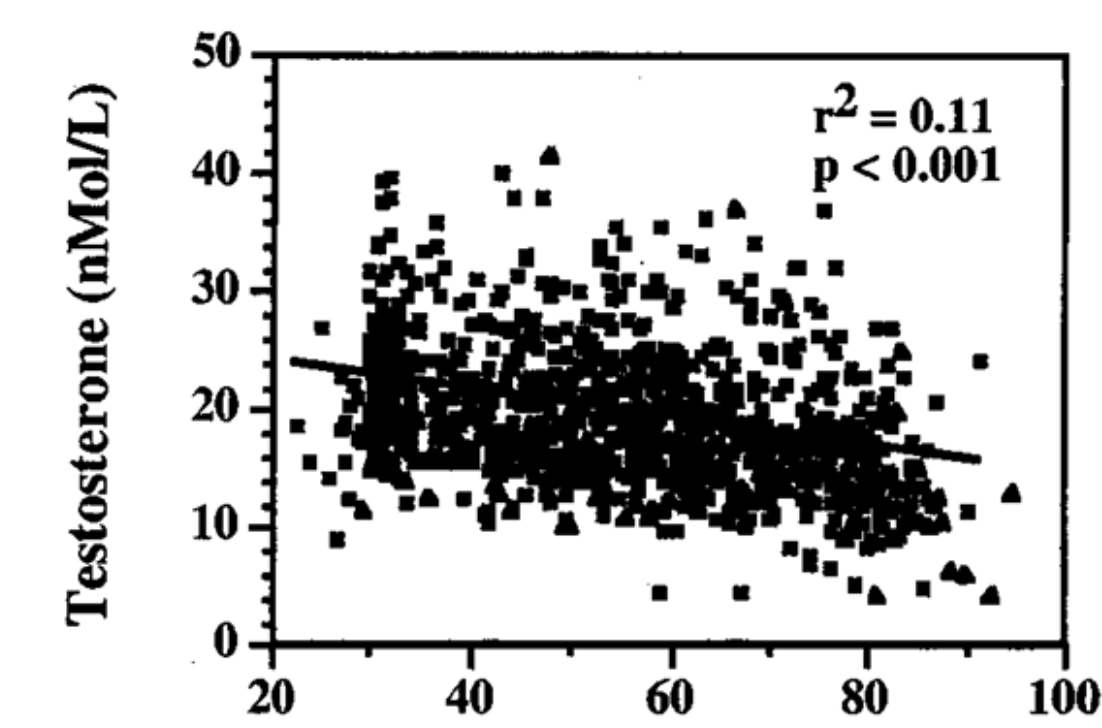

Both total testosterone and bioavailable testosterone declined steadily from age thirty to ninety, with steeper declines in bioavailable testosterone, even after accounting for obesity, chronic illness, medications, smoking, and alcohol use, suggesting that these declines were independently caused by aging. The figure below depicts these results.

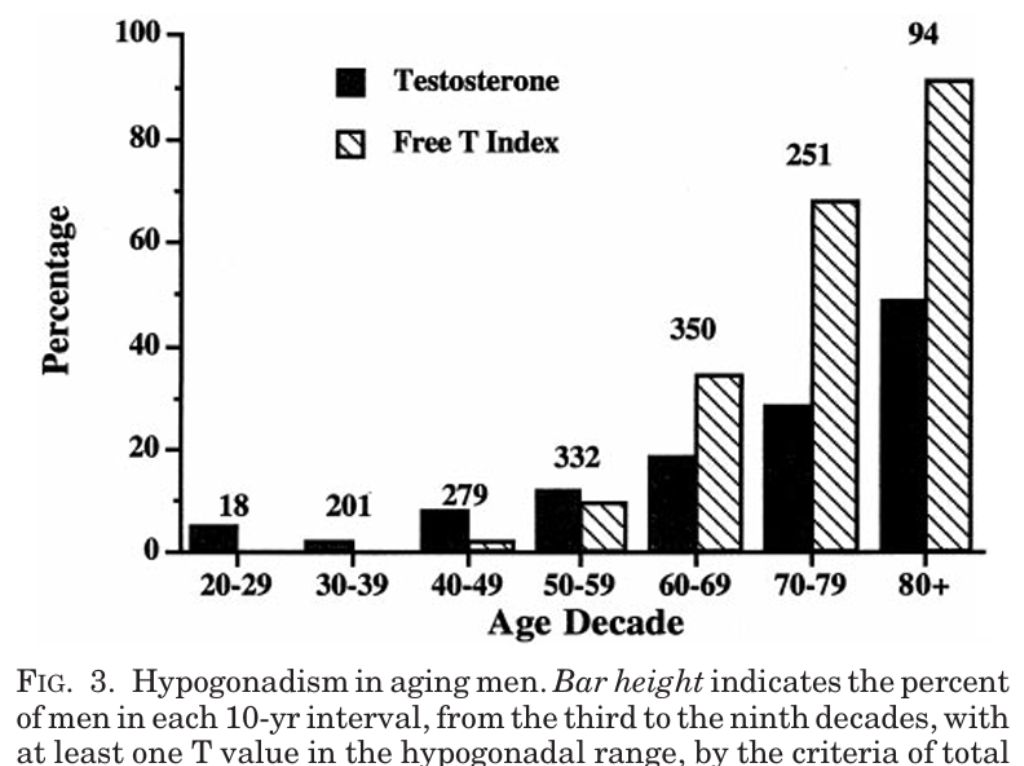

The prevalence of hypogonadism (clinically low testosterone) increased as men got older, from about 20% in men over 60, 30% over 70 and 50% over 80.

Bar height indicates the percent of men from each age decade with at least one testosterone value in the hypogonadal (low) range, for total testosterone (dark) and free testosterone (striped) respectively.

Key Quote

"Results strongly support the concept of an effect of aging to lower both total and bioavailable circulating T levels at a relatively constant rate, independent of obesity, illness, medications, cigarette smoking, or alcohol intake. In addition, our findings suggest that a significant proportion of men over 60 yr of age have circulating T concentrations in the range conventionally considered to be hypogonadal."

Strengths & Weaknesses

There is one hiccup in this study worth mentioning for those of you who are detail-oriented. Since the blood samples used in this study were frozen for decades, there was some degradation of SHBG, which made it initially appear that samples from 1961–1975 had 40% higher testosterone levels than samples from 1985–1995, which would have exaggerated the age-related declines. To ensure accuracy, researchers had to statistically adjust all values to account for this technical error.

Conclusion & Research Context

This study provided evidence that total and free testosterone decline consistently from age 20 onwards, leading to a progressively increasing likelihood of developing low testosterone in geriatric years.

The second major landmark study supporting the notion of testosterone decline with age was called…

Age trends in the level of serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts male aging study (Feldman et al., 2002)

Design

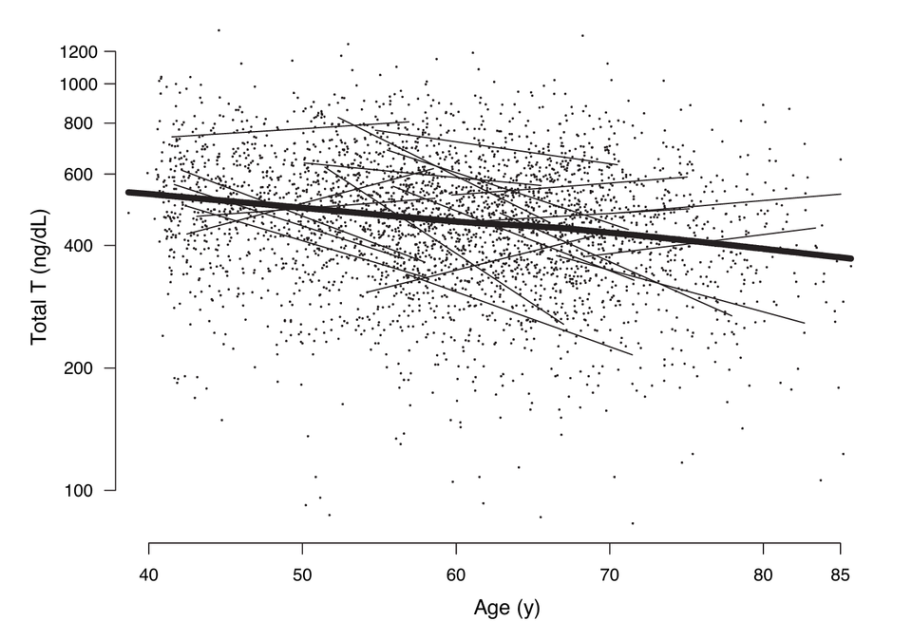

This study followed 1,156 men aged 40-70 (mean 55 years old at baseline) enrolled in the MMAS across a 7-10 year period.

Key Findings

Total testosterone declined 1.6% per year, and free testosterone declined 2-3% per year.

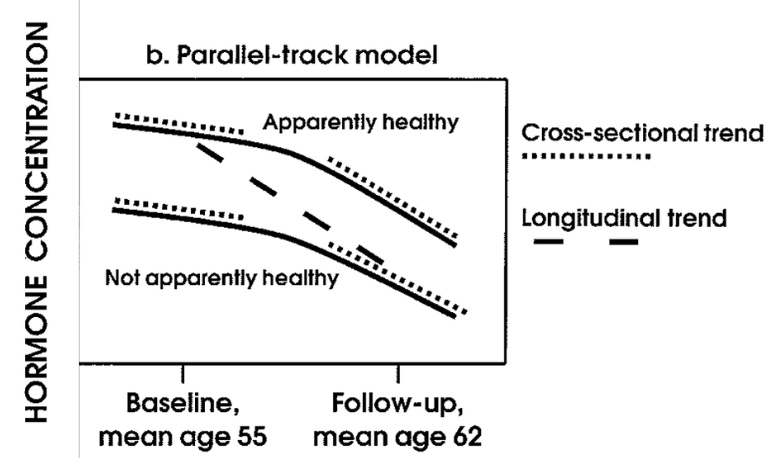

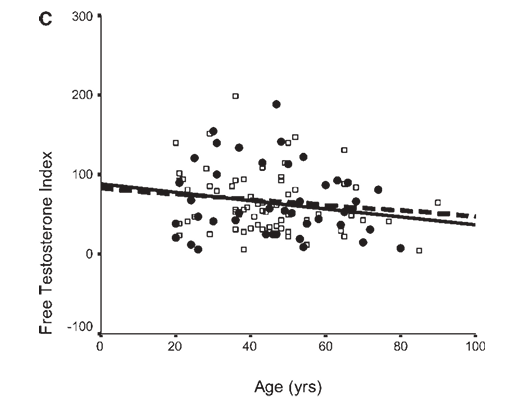

Men who were of "apparent good health,” defined as the absence of chronic illness, medication, obesity, or excessive drinking, had 10-15% higher testosterone levels, but the rate of decline still remained the same, as shown in the figure below.

Key Quote

“The paradoxical finding that longitudinal age trends were steeper than cross-sectional trends suggests that incident poor health may accelerate the age-related decline in androgen levels.”

This means that testosterone levels declined faster when observed longitudinally (in the same individual over time) as opposed to cross-sectionally (comparing levels in older vs younger men at the same point in time), indicating that poor health causes testosterone levels to decline faster than aging alone would predict.

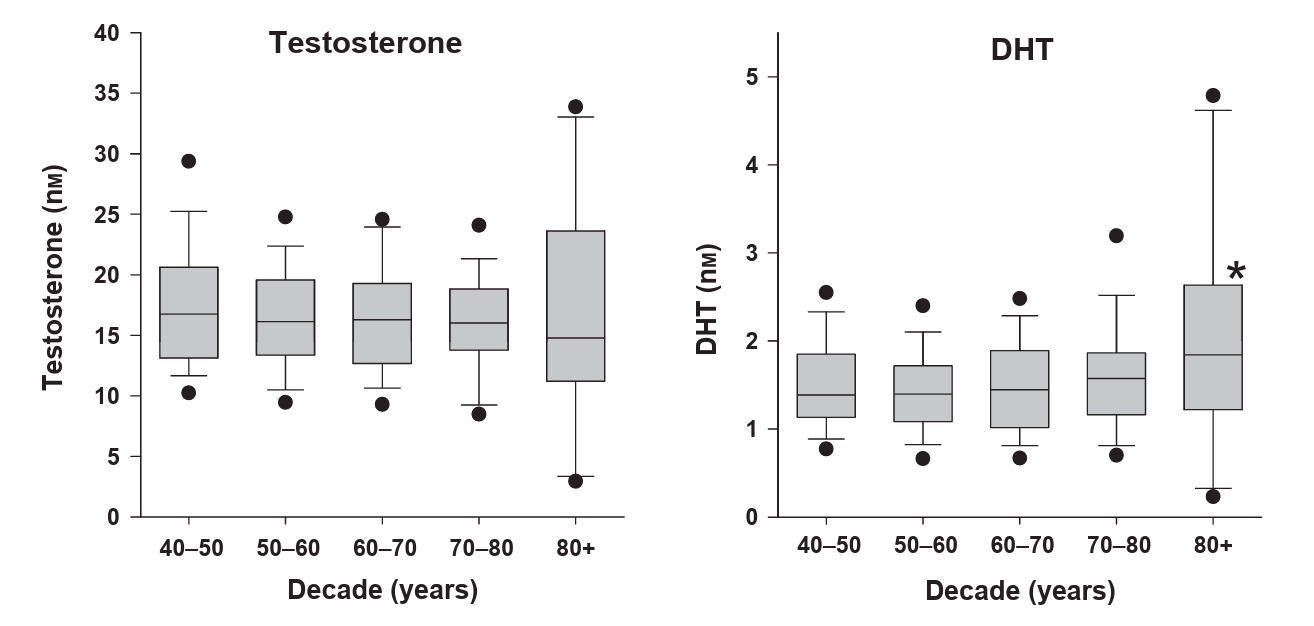

Fascinatingly, Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) increased 3.5% per year.

The researchers hypothesized that this may be the body’s way of compensating for lower overall testosterone production. By converting testosterone into its more potent version, the total androgenic effect can be maintained even as the total amount of available testosterone diminishes.

Conclusion & Research Context

Although good health keeps levels 10-15% higher, and the development of poor health accelerates declines, both total and free testosterone still declined from mid-life onward, but notably, the body seems to compensate for this by upregulating DHT production to exert equivalent androgenic effects with less raw material.

In contrast to the BLSA study, which showed significant declines in total and free testosterone regardless of health status, this study made a stronger case for the benefit of good health, but still revealed a seemingly inevitable decline.

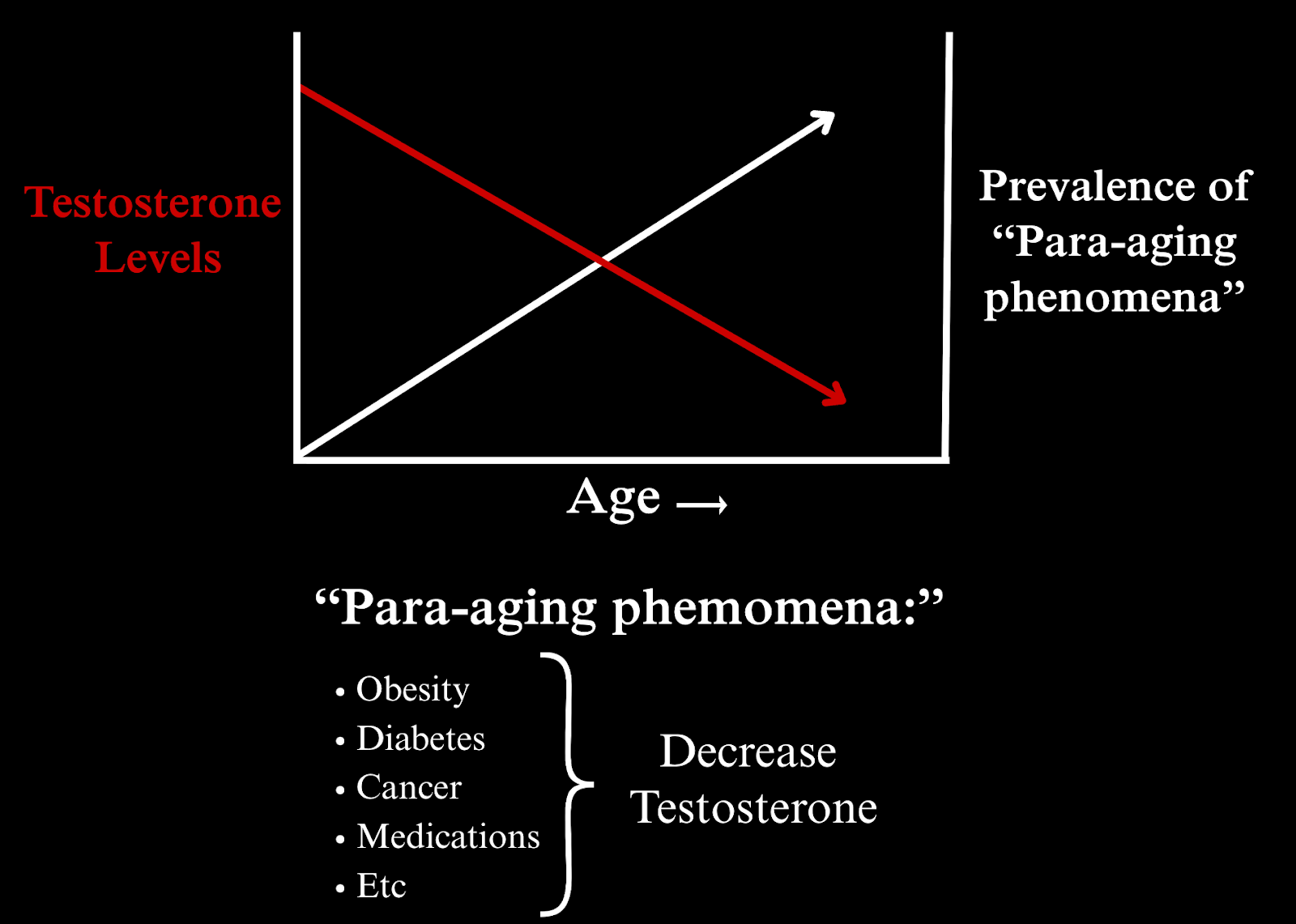

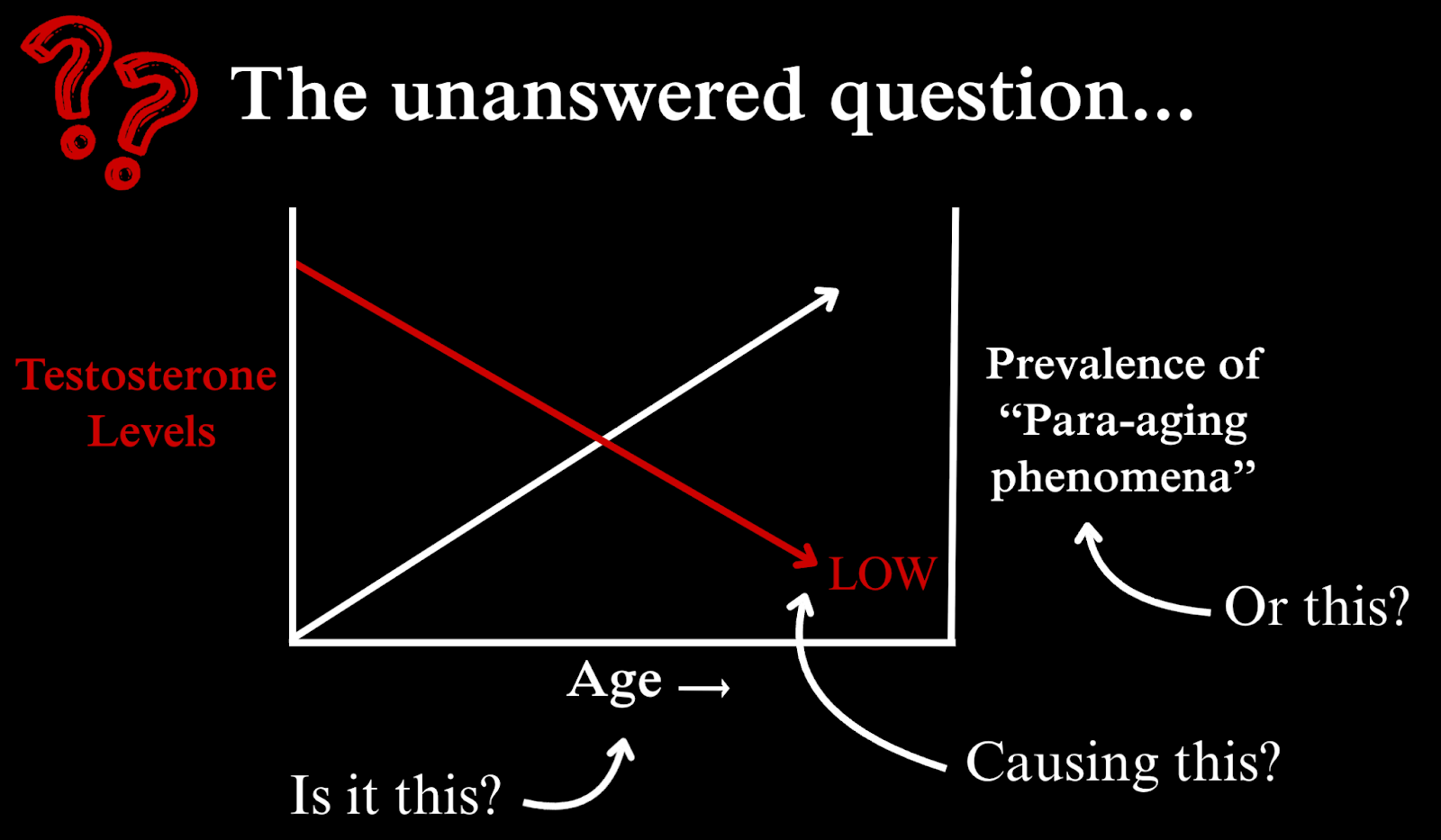

Although these two studies made an effort to account for the effect of health status, up to this point, it was still unclear the degree to which age-related declines in testosterone were intrinsic to normal aging itself versus decrements in overall health that just so happen to be more common with aging, called “para-aging phenomena” (conditions that are more prevalent among, but not specific to, older adults, like cancer, alzheimer's, etc).

There are two reasons why this difference was still unclear:

- The parameters used to define health in these studies were vague.

Feldman et. al even mentioned that...

“Our indicator of apparent good health was a crude composite based on fundamental data rather than on detailed clinical measures.”

- The men in these studies were simply lumped into “healthy” and “unhealthy” categories based on these “crude” criteria, and the specific effects of individual health factors were not quantified.

I don’t point this out to discredit the integrity of these studies. Most studies only focus on one finding at a time, and the objective of these studies was just to discover if testosterone levels decline with age.

I point this out to highlight the importance of gaining a more complete understanding of a body of research by reading multiple studies and making connections between them before drawing conclusions about a particular topic.

Clarifying whether or not these observed declines in testosterone were caused by age or by conditions that are more prevalent in older people is crucial for informing what men like you, who are interested in preserving your testosterone levels as you age, can do about it, because aging is not in your control, but your health absolutely is.

In that light, a few years after the Feldman and Hardman studies were published, one of my favorite researchers of all time, Thomas Travison, was not satisfied with the gap in our understanding of the influence of health and lifestyle factors on testosterone decline with age, so he and his colleagues took it upon themselves and to conduct their own study to investigate the relative effects of health, lifestyle, and aging on testosterone levels over time.

Their objective was to quantify the percent of declines in testosterone that were caused by aging in isolation, versus individual health and lifestyle variables.

Unlike the previous studies, they weren’t just labelling men healthy and unhealthy and comparing their rates of testosterone decline with age; they were separating individual health and lifestyle factors one by one and measuring the effect they had on testosterone levels over time.

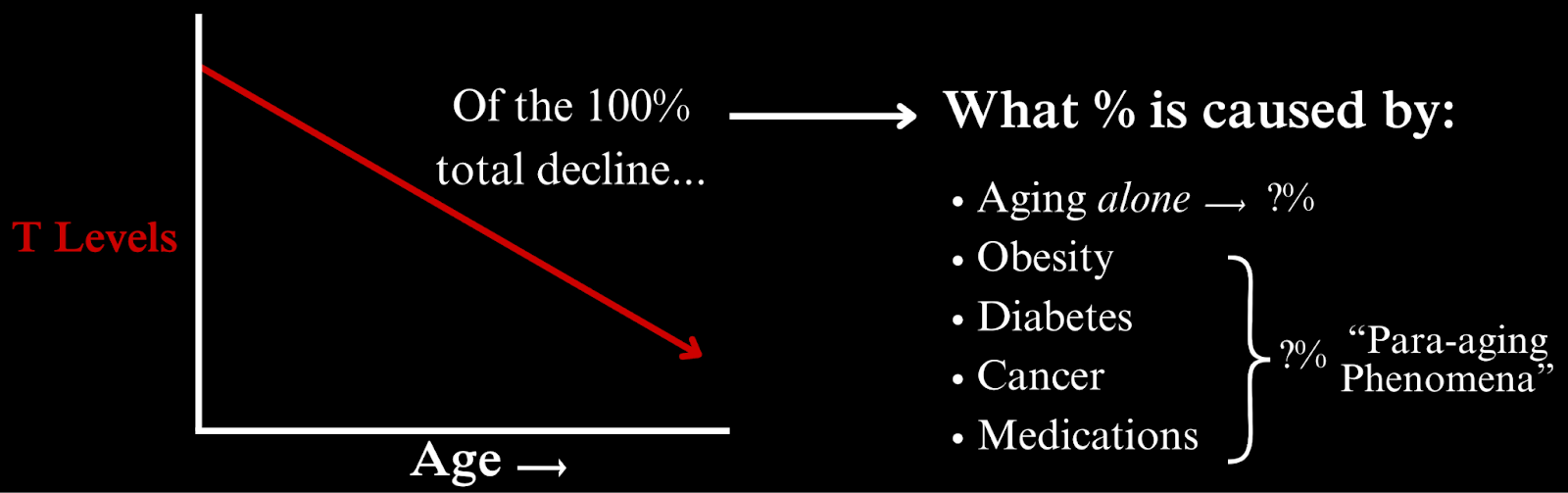

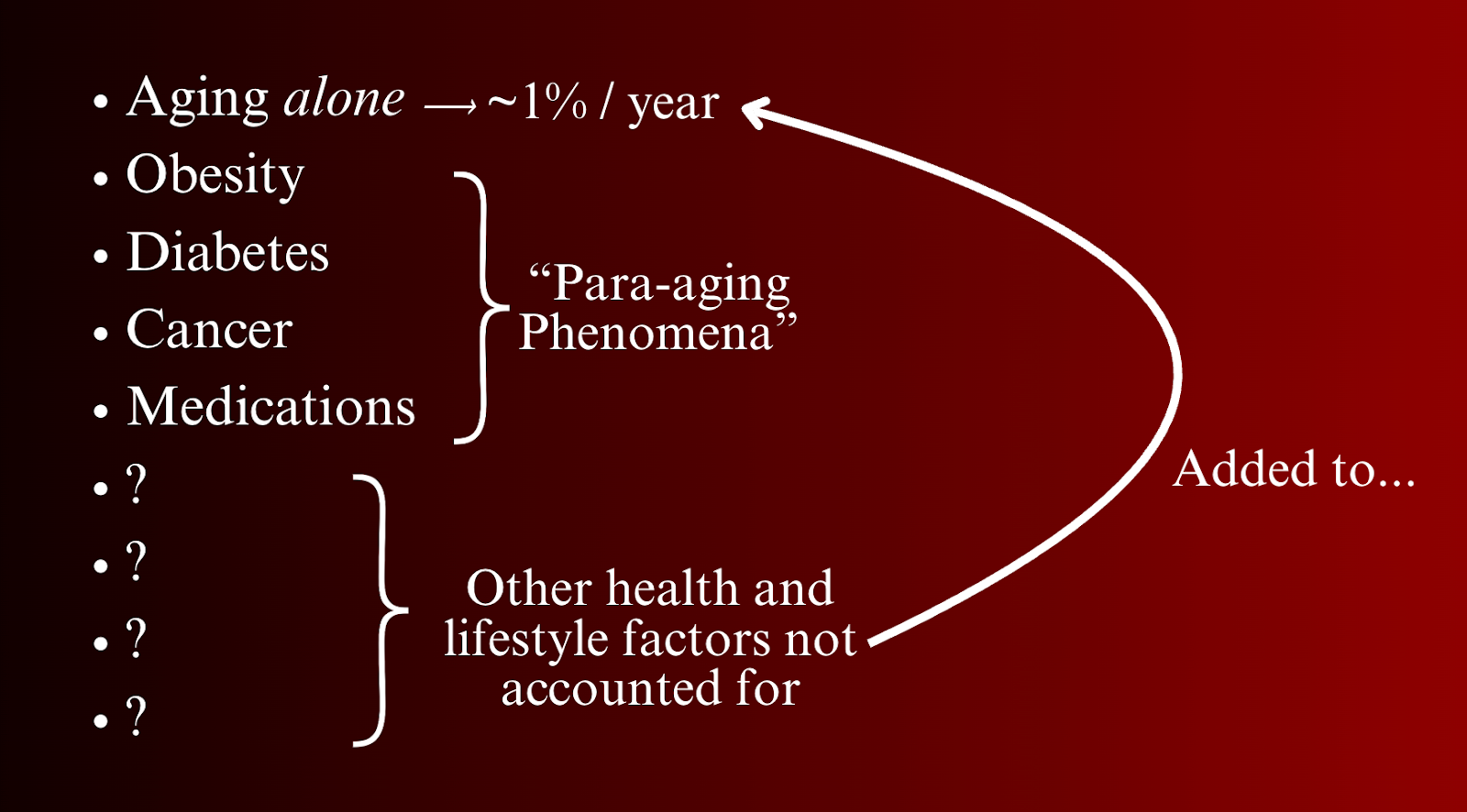

The Relative Contributions of Aging, Health, and Lifestyle Factors to Serum Testosterone Decline in Men (Travison et al., 2007).

Design

Travison and his colleagues used the same longitudinal testosterone data from the MMAS, but they conducted a comprehensive statistical analysis to determine the influence of numerous health and lifestyle factors (also captured by the MMAS) on those readings, such as obesity, diabetes, cancer, smoking, depression, and many more.

Key Findings

Aging alone was associated with a 10.1% reduction in total testosterone and 23.8% reduction in free testosterone per decade (-1% and -2.38% per year respectively).

However, the cumulative effect of all the health and lifestyle factors they measured drove down testosterone levels more than aging did. Here are some examples of those factors:

- Obesity: Men who were not obese at baseline but later became obese had 12% lower total testosterone levels, equivalent to a decade of aging.

- Chronic Illness: Subjects who had developed any chronic illness had -13.1% lower free testosterone levels at follow up.

- Diabetes: Of all the chronic diseases observed, diabetes had the most detrimental effect on testosterone levels. Men diagnosed with diabetes between baseline and follow-up were over 2.5 times as likely to have testosterone levels in the hypogonadal range (below 300 ng/dL, considered clinically low).

- Polypharmacy: The simultaneous use of multiple prescription drugs was associated with “substantially accelerated T decline.” Whether it was the drugs themselves or the conditions they were prescribed to treat was not specified, but it has been shown that certain pharmaceuticals can suppress androgen production (17).

- Loss of Spouse: Men whose wives died between baseline and follow-up had declines in testosterone comparable to 10 years of aging, about the same effect as obesity, highlighting the powerful yet often overlooked influence of psychological wellbeing on testosterone levels.

- Loss of Employment: Losing one’s job was shown to have a measurable negative effect on testosterone levels as well.

Because of the powerful influence of health and lifestyle factors, Travison and colleagues concluded that:

“Although hormone declines appear to be an integral aspect of the aging process, rapid declines need not be dismissed as inevitable, as age-related hormone decline may be decelerated through the management of health and lifestyle factors.”

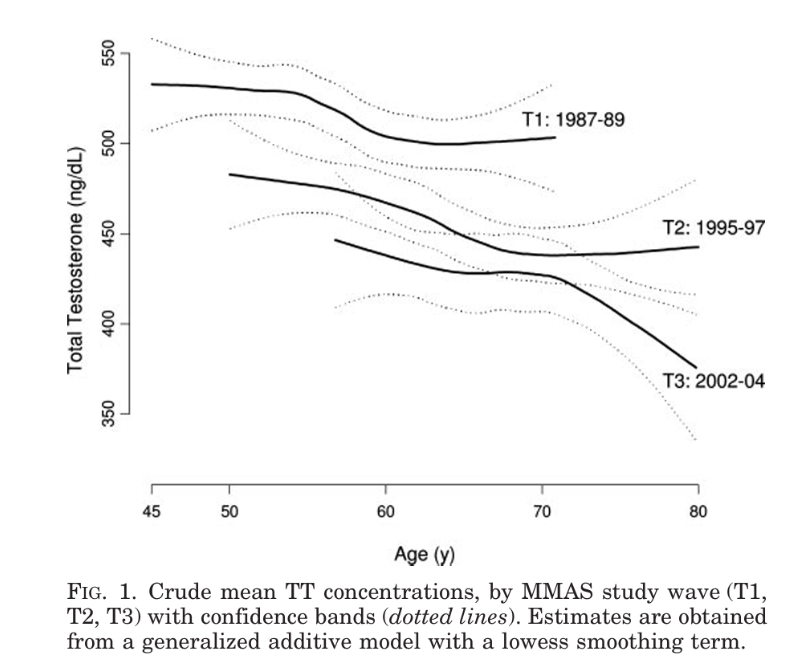

Fascinatingly, while conducting this study, Travison simultaneously produced another study using the same data, which ended up becoming a landmark study showing that testosterone levels are declining in men of all ages at the societal level (19).

Travison mentioned that these societal level testosterone declines may have exaggerated the declines that seemed to be associated with age in the present study.

Moreover, Travison pointed out that there are far too many health and lifestyle measures that may influence testosterone levels than could possibly be measured in one study, and so the effects of any variables they didn’t account for would have been ascribed to aging.

Thus, the true effect of health and lifestyle is almost certainly greater than what they reported, and the influence of age was likely inflated as a result.

Key Quote:

“Emerging evidence of a population-level decline in serum T over calendar time implies that estimates of T declines associated with male aging may themselves be biased. As such, the overall contributions of true health and lifestyle may exceed even the marked effects described in this study.”

Conclusion & Research Context

Travison’s study showed that, although there are noteworthy declines in testosterone caused by aging alone, they are probably exaggerated by testosterone levels falling in the overall population, and by the fact that not every health and lifestyle factor that affects testosterone levels could be accounted for.

Most importantly for you, this work revealed that the influence that health and lifestyle factors have on testosterone levels is greater than was originally reported and is greater than aging itself; an empowering finding because although nobody has control over their age, all of us have control over our health and lifestyle.

That and the comprehensive inclusion of numerous health and lifestyle factors coupled with the precise quantification of their effects on testosterone levels makes this a cornerstone study for anyone interested in offsetting testosterone decline with age.

As promising as Travison’s work is, the story doesn’t end there. Later research showed that age-related testosterone decline could be reversible…

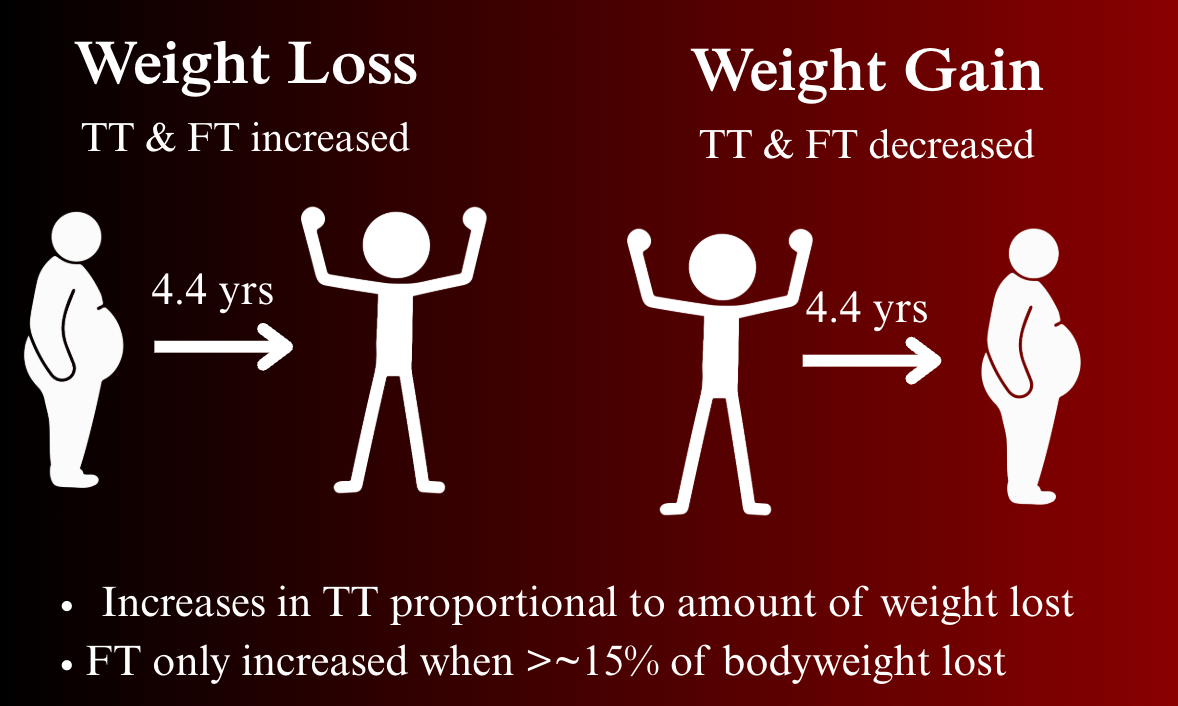

Age-associated changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular function in middle-aged and older men are modified by weight change and lifestyle factors: longitudinal results from the European Male Ageing Study (Camacho et al., 2013).

The European Male Ageing Study (EMAS) is essentially the European version of MMAS and BLSA: A multicenter, population-based cohort of over 2,300 men aged 40–79 from eight European countries: Florence (Italy), Leuven (Belgium), Lodz (Poland), Malmö (Sweden), Manchester (UK), Santiago de Compostela (Spain), Szeged (Hungary) and Tartu (Estonia). It includes both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses to study aging-related changes in sex hormones and general health.

A preliminary cross-sectional study conducted in the EMAS sought to determine the extent to which health and lifestyle influence changes in reproductive hormones (22). The results were longitudinally delineated in the study below…

Design

Reminiscent of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study, the study below sought to validate these early findings using longitudinal data from the same EMAS cohort. 2,395 men (aged 40–79) had baseline and follow-up hormone measurements 4.4-years later. Yearly changes in total testosterone, free testosterone, SHBG, and LH were calculated.

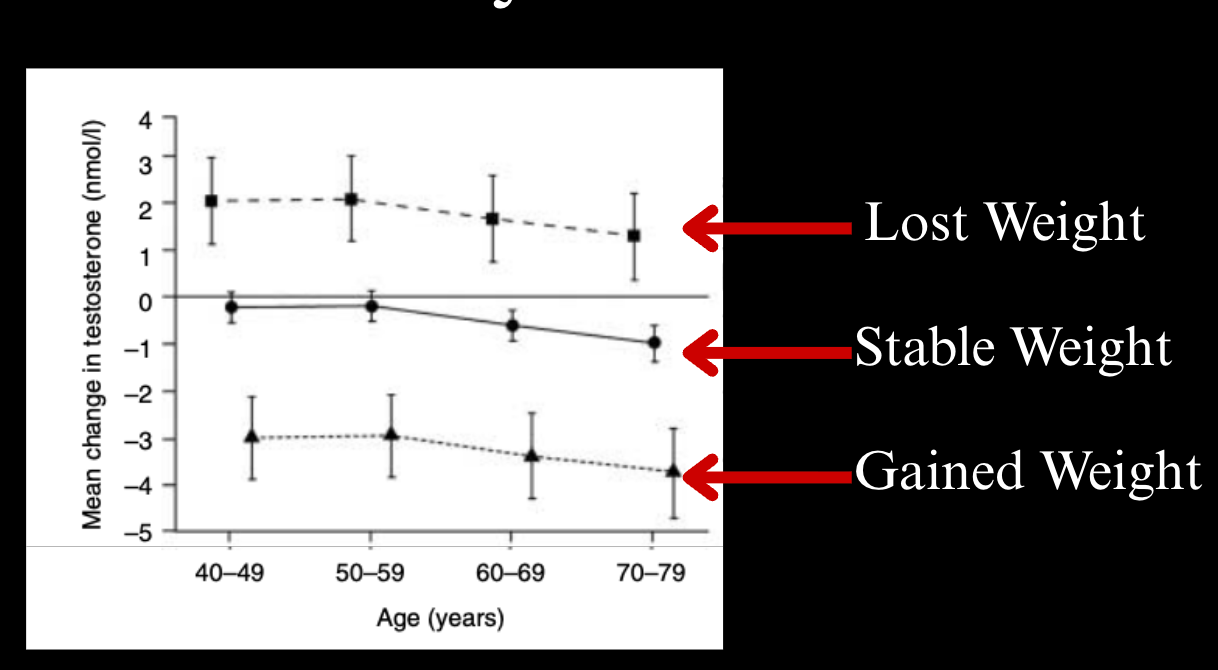

Key Findings

Men who lost weight increased their total testosterone levels above baseline, whereas men who gained weight had decreased total testosterone levels below baseline.

The magnitude of testosterone change directly corresponded with the amount of weight lost or gained; the greater the percentage of weight men lost, the higher their testosterone levels rose, and vice versa.

Key Quote:

“The apparent reversal of the age-related decline in testosterone and FT with weight loss, and its exaggeration with weight gain, reaffirm our previous suggestion that decreasing testosterone with ageing is not inevitable but potentially preventable and reversible with weight management."

Free testosterone was a bit more stubborn; increases were only observed when men lost 15% or more of their body weight.

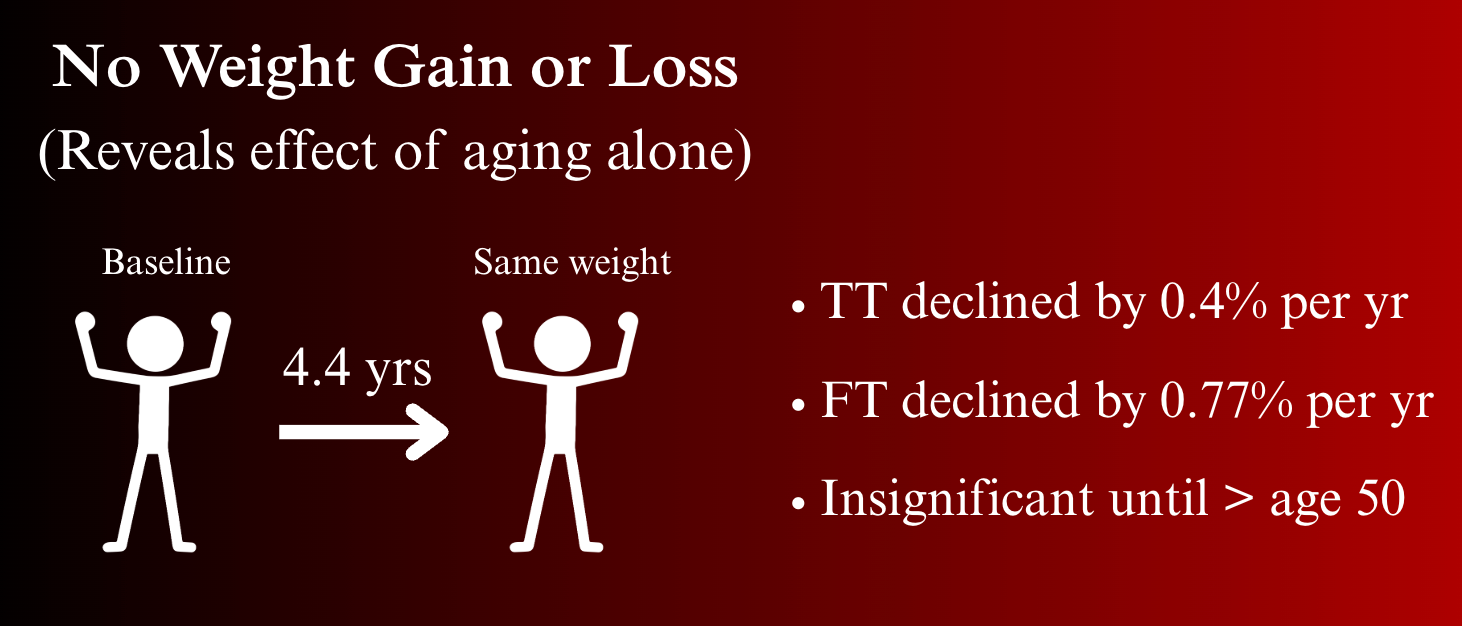

Men whose weight remained stable were of special interest because, after adjusting for the other health and lifestyle factors, any observed changes in their testosterone levels over time were attributable to aging itself. In these men, total testosterone declined by 0.4% per year, and free testosterone declined by 0.77% per year, but declines didn’t become significant until after age 50.

The top lines show men who lost weight, the middle lines show men whose weight remained stable, and the bottom lines show men who gained weight.

Interestingly, changes in number of comorbid conditions or physical activity were not significantly linked to hormone changes, which contrast the findings from other studies.

The average duration of follow-up of 4.4 years is relatively short in the context of the aging process. Longer follow-up with subsequent rounds of assessment would be ideal to define the long-term trajectory of testosterone levels more definitively.

Conclusion & Research Context

Age-related declines in testosterone were smaller and occurred decades later than those reported in early research, and declines were both preventable and reversible with weight management.

It’s interesting that age-related testosterone declines in European men were slower and occurred later in life than declines in American men. Europeans also have longer life expectancies than Americans (13).

Might this be because Europeans live healthier lifestyles? Are there other cultural differences at play?

While these findings underscore the fact that testosterone decline with age is a variable phenomenon, they still showed that testosterone levels do decline with age, but other research shows that testosterone levels don’t decline at all…

Serum testosterone, dihydrotestosterone and estradiol concentrations in older men self-reporting very good health: the healthy man study

Design

This study was conducted on 325 Australian men aged 40+ who self-reported excellent health.

Each participant gave nine blood samples over 3 months for analysis by a highly accurate assay, and the testosterone levels of men in younger age groups were cross-sectionally compared to the levels of men in older age groups.

Key Findings

In these “exceptionally healthy” men, both total and free testosterone did not change from age 40 to until after age 80, when free testosterone started to decline.

Key Quotes:

“Serum T displayed no decrease associated with age among men over 40 years of age who self-report very good or excellent health.”

“Calculated FT was not significantly different until it decreased in the 9th decade.”

This study also reported mild increases in DHT with age, but not quite to the same magnitude as those reported by Feldman et al.

Although this study had a relatively small sample size and, cross-sectional, and calculated free testosterone instead of directly measuring it (which can be less accurate), the repeated testosterone measurements provided highly accurate representations of the men’s 3-month averages, not just a single snapshot in time (which can be corrupted by acute hormonal fluctuations).

And despite the fact that men enrolled in this study all self-reported good health, 11% were obese, and 19% had high blood pressure (rates still lower than the general population), but their testosterone levels prevailed nonetheless, indicating a possible psychological effect wherein the belief that one is exceptionally healthy may improve androgen profiles.

Conclusion & Research Context

The researchers concluded that age-related declines may be due to the accumulation of comorbidities rather than aging itself.

This is one of the only studies to show no declines in free testosterone until very late in life (80+). Most other studies show that, even if total testosterone remains stable, free testosterone almost always declines.

The hypothesis that testosterone doesn’t decline with age was reaffirmed by a study conducted two years later…

A Validated Age-Related Normative Model for Male Total Testosterone Shows Increasing Variance but No Decline after Age 40 Years (Kelsey et al., 2014)

Design

This study is particularly powerful because it amalgamates findings from 13 other studies, (including data from the BLSA & MMAS) encompassing over 10,000 males from 3-101 years old.

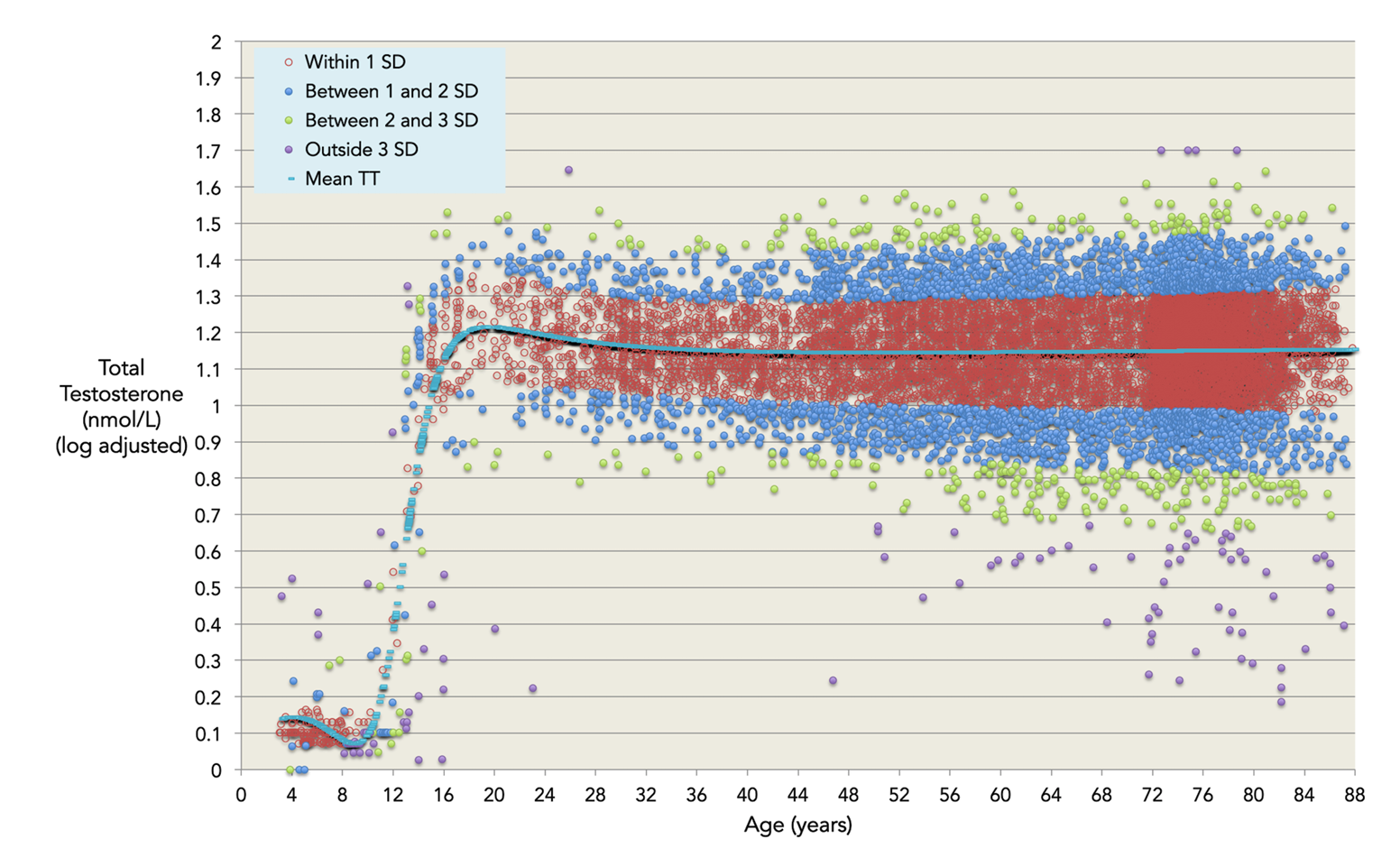

Key Findings

According to this combined model, total testosterone peaks at age 19 (~15.4 nmol/L), falls slightly by age 40 (~13.0 nmol/L), then stabilizes for the rest of life, but the percentage of men with abnormally high or low testosterone levels increases with age.

Another way to put this is that the average 40 year old and the average 80 year old have roughly the same mean testosterone level, but there are more 80 year olds with testosterone levels above or below average.

Key Quotes:

“We find no evidence that TT declines in the average case after the age of 40 years for ageing males. We do find that the prevalence of higher and lower testosterone levels increases with age.”

The researchers calculated that around 41% of this variation between men is due to age, and that 59% is due to other factors such as lifestyle and health status.

“Around 41% of the variation in serum TT throughout healthy male life is due to age alone, and that 59% in the variation is therefore due to other factors such as lifestyle, anthropometry and health status.”

This figure from the study shows that mean testosterone levels flatline from age 40 onwards, but there are more outliers (purple & green) in older age groups.

Because of the fact that the standard deviation of testosterone levels increases with age, the researchers postulated that past studies (namely Harman et. al 2001) showing a higher likelihood of hypogonadism in older men may be due to the greater variation in testosterone levels among older men, not necessarily because testosterone declines with age.

“Our model provides a coherent explanation for the widely believed but incorrect assertion that the prevalence of male hypogonadism increases from 12% in men in their 50s to 49% in men in their 80s.”

Conclusion & Research Context

Although some compromises that slightly reduce data accuracy must be made when combining findings from over a dozen studies, this study provided solid statistical evidence that total testosterone does not decline with age.

Despite its statistical power, this study only plotted total testosterone; it doesn’t provide any data on free testosterone, but a similar, and even larger study, did…

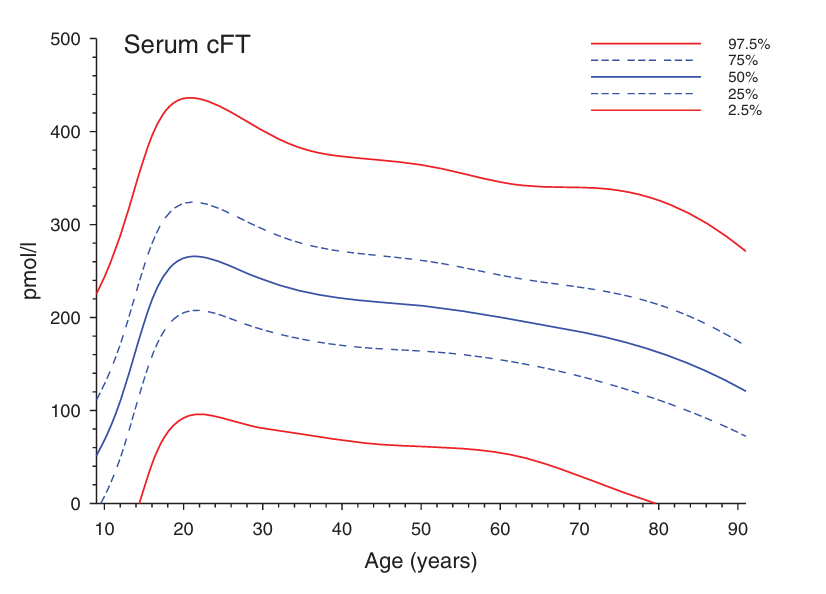

Estimating age-specific trends in circulating testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin in males and females across the lifespan (Handelsman et al., 2015)

Design

This study observed age differences in testosterone test results from 61,131 males aged 10-90 from a large clinical laboratory in Melbourne Australia from 2007–2013. No interventions were done, it was purely an observational study looking at routine lab results.

Key Findings

After plotting the data, the researchers found that after peaking around age 20, total testosterone levels remain relatively stable until men reach their eighties. Calculated free testosterone mirrors total testosterone but declines around age 60 due to rising SHBG.

Key Quote:

“The minimal decline in serum testosterone between the ages of 35 and 65 years is striking…Only after the age of 80 years is there a more pronounced, definite decline in circulating testosterone, consistent with many other studies, and consistent with the impact of cumulative effects of the co-morbidities of male ageing rather than age itself.”

The main limitation of this study is that the data come from individuals who had a clinical reason to check their testosterone levels, meaning some men might have conditions that negatively affect testosterone levels, so it’s not exactly representative of the general population. In this light, the fact that testosterone levels remained stable with age is even more eye opening.

Other limitations include the fact that no other information was available on these patients, just their testosterone test results, so health and lifestyle factors could not be accounted for.

Additionally, this is a cross-sectional study, so trends were drawn by comparing testosterone levels between older and younger subjects, which is less precise than tracking the same individuals over time.

Conclusion & Research Context

That said, the sheer volume of data used in this study and the fact that both total and free testosterone levels remained stable until geriatric years provides more strong evidence for the hypothesis that testosterone doesn’t significantly decline with age.

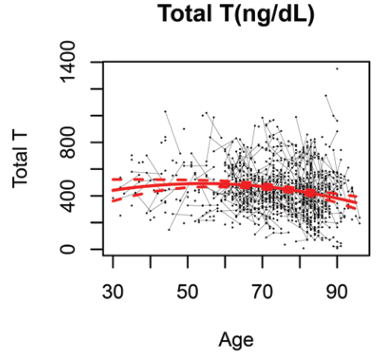

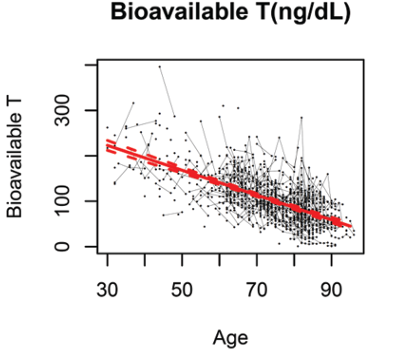

Bioavailable Testosterone Linearly Declines Over A Wide Age Spectrum in Men and Women From The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (Fabbri et al., 2016)

At the time of this writing, this is the most recent study I could find that discovered a relevant novel finding.

Design

The objective of this study was to characterize age trajectories of total and measured bioavailable testosterone in men (and women), with a special emphasis on the oldest-old (aged 65+), covering a gap in past research.

Measured bioavailable testosterone (mBT), which, as the name implies, involves actually measuring bioavailable testosterone levels, is the gold standard for determining bioavailable testosterone levels with the utmost accuracy, because calculating bioavailable testosterone (cBT) is known to be less accurate.

The study used 10 years of longitudinal data following 788 participants aged 30-98 enrolled in the BLSA, with follow-up intervals every 2 years on average.

Key Findings

Total testosterone remained stable until about age 70 then progressively declined at older ages, whereas measured bioavailable testosterone declined linearly throughout adult life, mostly in line with rises in SHBG.

Key Quote:

“The evident flatness of TT in middle-aged males contrasts with the traditional belief that TT starts to progressively decline after the age of 30–40 years.”

Conclusion & Research Context

The lack of decline in total testosterone levels until very late age re-affirms the findings from Kelsey et. al and Handelsman et al, and the finding that bioavailable testosterone declines linearly is in agreement with other studies showing more profound declines in free testosterone with age.

The decent sample size, repeated follow-up testing, 10 year time, duration, and longitudinal design all make this study’s findings quite sound.

That said, its most notable “weakness” is that it only measures how hormone levels change with age. Since the influence of other variables were not accounted for, we can’t know the degree to which declines were driven by age itself versus health and lifestyle variables.

This is particularly noteworthy because once again, total testosterone levels still didn’t decline with age even though health and lifestyle factors weren’t accounted for, and since past studies have shown that such factors can have an even more profound effect than aging itself, it stands to reason that the age-related declines observed in this study are likely significantly greater than the true effects of aging alone.

That’s the end of the story on the research thus far in industrialized nations, but it’s not the end of the story on the research on testosterone and aging…

Research In Non-Industrialized Subsistence Populations

Research has been conducted on non-industrialized subsistence populations whose livelihoods depend directly on extracting or cultivating natural resources from their immediate environment to meet basic survival needs.

Most of the chronic diseases shown to contribute to testosterone decline with age in industrialized nations, such as obesity and diabetes, are byproducts of modern living, due to a sedentary lifestyle, high processed food intake, exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals, etc.

Both the chronic conditions themselves and the aspects of modern living that cause them are comparatively absent in subsistence populations.

Thus, subsistence populations are of special interest in research on aging and testosterone levels because their lifestyles are reminiscent of how human beings evolved, so they can give us insights into the degree to which age-related declines in testosterone in industrialized nations are due to the deleterious aspects of modern lifestyles versus aging itself.

Population variation in age-related decline in male salivary testosterone (Elison et al., 2002)

Design

This study directly compared data on age variation in free testosterone levels from four different populations:

- 33 Lese horticulturalists from the Congo

- 39 Tamang agropastoralists from central Nepal

- 45 Ache foragers from southern Paraguay

- 106 Residents of Massachusetts, USA

All the testosterone samples were collected using the same protocols in the same laboratory to ensure consistency.

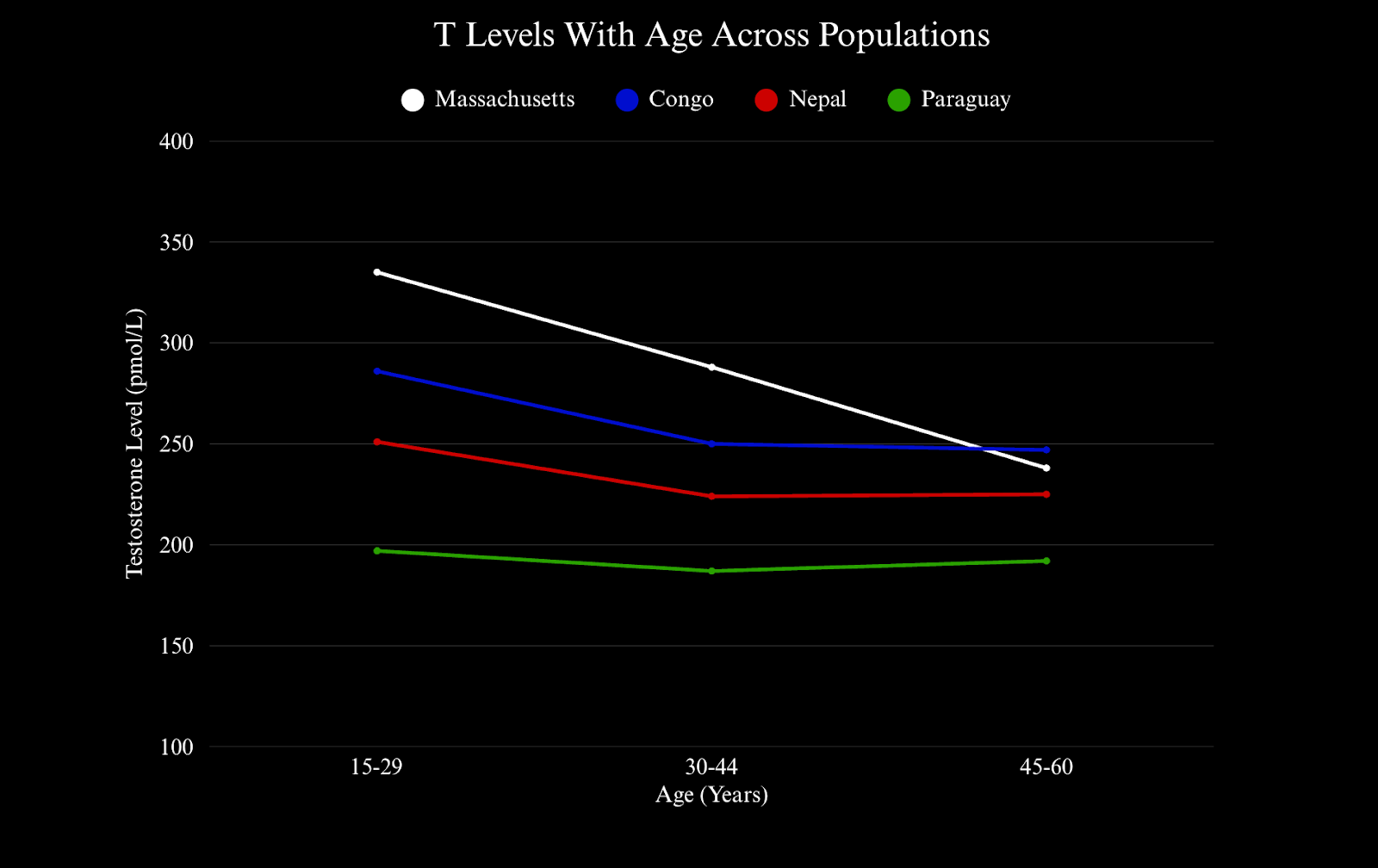

Key Findings

Age-related testosterone decline was most significant in the residents of Massachusetts, less significant in the Lese (Congo), and not statistically significant among the Tamang (Nepal) or Ache (Paraguay).

The researchers summarized that:

“The most important general observation from these data is that age-related declines in free testosterone is not a uniform characteristic of all populations.”

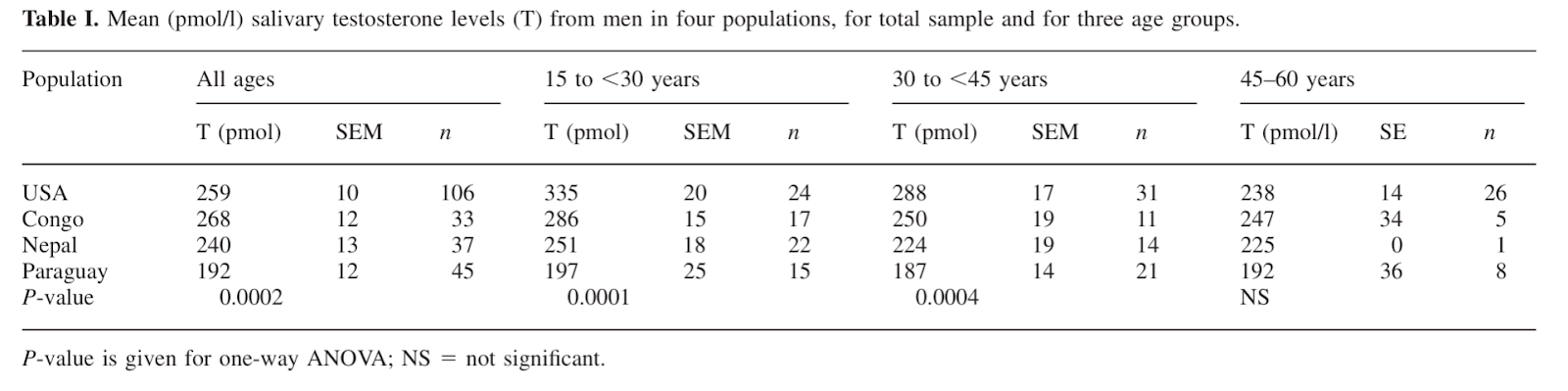

This is an exact visual representation of the study’s findings. I created this figure by plotting the mean testosterone levels from the men in each population at three age groups (15-20, 30-44, 45-60). X axis = age (years). Y axis = testosterone level (pmol/L).

This is the raw data from the study I plotted in the figure above.

It’s worth noting that average testosterone levels are lower in the subsistence populations than in industrialized nations, largely due to food scarcity and immune system upregulation to ward off pathogens.

The researchers inferred that the lack of testosterone decline in the subsistence populations could be due to the small sample sizes, or because they have lower levels in younger years, not necessarily because they are exempt to the effects of aging.

This hypothesis is supported by the fact that testosterone levels all converged around the same low levels in later years, it’s just that the men in subsistence populations didn't have as far down to go because their baseline testosterone levels were lower to begin with.

Conclusion & Research Context

We can’t know for sure that the testosterone levels of men in subsistence wouldn’t decline if their baseline levels were higher, so the fact that their free testosterone levels remain stable across their lifespans is remarkable, especially because studies in western men consistently show that free testosterone in particular declines linearly across adulthood.

Age-Related Changes in Testosterone and SHBG Among Turkana Males (Campbell et al., 2006)

Design

The objective of this study was to determine age-related changes in biologically available testosterone among Turkana of northern Kenya.

The Turkana are pastoralists, meaning they live off the land and their livestock for survival, with little exposure to modern ways of living (aside from their AK47s apparently).

The researchers took hormonal measures from a total of 176 men aged 20-90 years old; 104 were nomadic, meaning they traveled with their livestock, whereas 72 were settled, meaning they stayed in one location, with more consistent access to food, water, and shelter.

Key Findings

Total Testosterone did not decline significantly with age in either group, but the nomads had notably higher average total testosterone levels.

Free testosterone showed a statistically significant decrease with age among the nomads (alongside concurrent increases in SHBG), but not the settled males.

The nomads produce testosterone just fine throughout their lives (as evidenced by unchanging total testosterone production), but seem to reduce its availability age (by reducing free testosterone).

Since the Turkana often face food scarcity, the researchers postulated that lower free testosterone in later ages could be advantageous for them because free testosterone increases metabolism, and thus, calorie requirements.

Conclusion & Research Context

These findings suggest that extreme stressors of any kind, whether it be hunger in the Turkana or obesity in Massachusetts, lead to reductions in free testosterone with age, even if total testosterone production can be maintained.

Other studies conducted on subsistence populations that didn’t explicitly investigate the relationship between aging and testosterone did observe a lack of connection between age and testosterone levels as a secondary finding (20, 21, 1).

One such study, titled Physical competition increases testosterone among Amazonian forager-horticulturalists (Trumble et al., 2012) reported that:

“Age was not associated with basal Tsimane T levels, or changes in T following competition. These results replicate those of previous studies suggesting that the typical pattern of decreasing T across the lifespan in industrialized populations may not be generalizable to forager-horticulturalist populations” (20).

With all of that research now fully unpacked, let’s tie it all together into one final verdict…

Research Summary

- Total testosterone remains stable well into your 70s-80s, especially in healthy men.

- DHT may slightly increase with age.

- Free and bioavailable testosterone seem to decline, even in healthy men, but the age at which declines begin, and their slope, is largely contingent upon overall health status.

Declines in free testosterone are particularly noteworthy because free testosterone is unbound and free to exert testosterone’s effects, so changes in its levels are directly felt in firsthand experience.

Free testosterone declines primarily because SHBG levels increase with age, which was one of the most common findings between all the studies.

So the body remains capable of maintaining testosterone production with age (as evidenced by unchanging total testosterone levels), but of the testosterone it produces, the body deactivates a greater proportion of it (via elevated SHBG production).

Since elevations in SHBG and the subsequent declines in free testosterone are observed in healthy men and subsistence populations, it appears that free testosterone decline is not a byproduct of poor health or modern living, but rather an intrinsic part of male aging, which begs the question…

Why does SHBG increase with age?

The answer to this question is a fascinating one, with implications that will completely transform how you conceive of the aging process in general.

As will be discussed in the next part of this article series, increases in SHBG may actually extend your lifespan…

Testosterone Transformation Academy

If you happen to be experiencing the effects of testosterone decline, and you believe it’s due to those health and lifestyle factors, I highly recommend you check out the Testosterone Transformation Academy; a men’s health coaching program I’ve developed that leverages scientific findings, like those described in this article, to help men optimize their testosterone levels naturally.

Optimize your testosterone levels naturally, using science.

Feel free to subscribe for more informational content!

References

- Bribiescas, R. G. (1996). Testosterone levels among Aché hunter-gatherer men: A functional interpretation of population variation among adult males. Human Nature, 7(2), 163–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02692109

- Camacho, E. M., Huhtaniemi, I. T., O'Neill, T. W., Finn, J. D., Pye, S. R., Lee, D. M., Tajar, A., Bartfai, G., Boonen, S., Casanueva, F. F., Forti, G., Giwercman, A., Han, T. S., Kula, K., Keevil, B., Lean, M. E., Pendleton, N., Punab, M., Vanderschueren, D., Wu, F. C., & EMAS Group. (2013). Age-associated changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular function in middle-aged and older men are modified by weight change and lifestyle factors: Longitudinal results from the European Male Ageing Study. European Journal of Endocrinology, 168(3), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-12-0890

- Campbell, B., Leslie, P., & Campbell, K. (2006). Age-related changes in testosterone and SHBG among Turkana males. American Journal of Human Biology, 18(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20468

- Cheng, H., Zhang, X., Li, Y., Cao, D., Luo, C., Zhang, Q., Zhang, S., & Jiao, Y. (2024). Age-related testosterone decline: Mechanisms and intervention strategies. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 22(1), 144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-024-01316-5

- Corona, G., Sforza, A., & Maggi, M. (2017). Testosterone replacement therapy: Long-term safety and efficacy. The World Journal of Men's Health, 35(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.5534/wjmh.2017.35.2.65

- Ellison, P. T., Bribiescas, R. G., Bentley, G. R., Campbell, B. C., Lipson, S. F., Panter-Brick, C., & Hill, K. (2002). Population variation in age-related decline in male salivary testosterone. Human Reproduction, 17(12), 3251–3253. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/17.12.3251

- Fabbri, E., An, Y., Gonzalez-Freire, M., Zoli, M., Maggio, M., Studenski, S. A., Egan, J. M., Chia, C. W., & Ferrucci, L. (2016). Bioavailable testosterone linearly declines over a wide age spectrum in men and women from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 71(9), 1202–1209. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw021

- Feldman, H. A., Longcope, C., Derby, C. A., Johannes, C. B., Araujo, A. B., Coviello, A. D., Bremner, W. J., & McKinlay, J. B. (2002). Age trends in the level of serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men: Longitudinal results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 87(2), 589–598. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.87.2.8201

- Gray, A., Feldman, H. A., McKinlay, J. B., & Longcope, C. (1991). Age, disease, and changing sex hormone levels in middle-aged men: Results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 73(5), 1016–1025. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-73-5-1016

- Handelsman, D. J., Sikaris, K., & Ly, L. P. (2016). Estimating age-specific trends in circulating testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin in males and females across the lifespan. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry, 53(3), 377–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004563215610589

- Harman, S. M., Metter, E. J., Tobin, J. D., Pearson, J., Blackman, M. R., & Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. (2001). Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 86(2), 724–731. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.86.2.7219

- Kelsey, T. W., Li, L. Q., Mitchell, R. T., Whelan, A., Anderson, R. A., & Wallace, W. H. (2014). A validated age-related normative model for male total testosterone shows increasing variance but no decline after age 40 years. PLOS ONE, 9(10), e109346. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109346

- Machado, S., Kyriopoulos, I., Orav, E. J., & Papanicolas, I. (2025). Association between wealth and mortality in the United States and Europe. The New England Journal of Medicine, 392(13), 1310–1319. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa2408259

- Mederos, M. A., Bernie, A. M., Scovell, J. M., & Ramasamy, R. (2015). Can serum testosterone be used as a marker of overall health?. Reviews in Urology, 17(4), 226–230.

- National Institute on Aging. (n.d.). About the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/labs/blsa/about

- O'Donnell, A. B., Araujo, A. B., & McKinlay, J. B. (2004). The health of normally aging men: The Massachusetts Male Aging Study (1987-2004). Experimental Gerontology, 39(7), 975–984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2004.03.023

- Smith, C. G. (1982). Drug effects on male sexual function. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 25(3), 525–531. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003081-198209000-00008

- Travison, T. G., Araujo, A. B., Kupelian, V., O'Donnell, A. B., & McKinlay, J. B. (2007). The relative contributions of aging, health, and lifestyle factors to serum testosterone decline in men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 92(2), 549–555. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-1859

- Travison, T. G., Araujo, A. B., O'Donnell, A. B., Kupelian, V., & McKinlay, J. B. (2007). A population-level decline in serum testosterone levels in American men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 92(1), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-1375

- Trumble, B. C., Cummings, D., von Rueden, C., O'Connor, K. A., Smith, E. A., Gurven, M., & Kaplan, H. (2012). Physical competition increases testosterone among Amazonian forager-horticulturalists: A test of the ‘challenge hypothesis’. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1739), 2907–2912. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.0455

- Vitzthum, V. J., Worthman, C. M., Beall, C. M., Thornburg, J., Vargas, E., Villena, M., Soria, R., Caceres, E., & Spielvogel, H. (2009). Seasonal and circadian variation in salivary testosterone in rural Bolivian men. American Journal of Human Biology, 21(6), 762–768. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20927

- Wu, F. C., Tajar, A., Pye, S. R., Silman, A. J., Finn, J. D., O'Neill, T. W., Bartfai, G., Casanueva, F., Forti, G., Giwercman, A., Huhtaniemi, I. T., Kula, K., Punab, M., Boonen, S., Vanderschueren, D., & European Male Aging Study Group. (2008). Hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis disruptions in older men are differentially linked to age and modifiable risk factors: The European Male Aging Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 93(7), 2737–2745. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-1972

- Yabluchanskiy, A., & Tsitouras, P. D. (2019). Is testosterone replacement therapy in older men effective and safe?. Drugs & Aging, 36(11), 981–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00716-2